Summary

A lot has been written about disruptors (and particularly digital disruptors) over the last couple of years. By necessity, many enterprises adopt a reactive approach to disruptors, but there are significant ways for enterprise business architecture (EBA) to underpin a stronger, more productive approach.

Enterprises tend to be considered as either digital predators or digital prey. A major differentiator between those who take advantage of disruption and those who fall victim to it is the extent to which they understand and take account of the business architecture for their whole ecosystem.

In order to do this, best practice suggests that the scope of EBA activities should be:

- Extended to accommodate systematic ‘horizon scanning’ for potentially relevant disruptors

- Deepened to ensure that full account is taken of the enterprise business model. This should include analysis not just of what the business does, but operational reasons (short term motivation) and strategic reasons (long term motivation) for doing it;

- Broadened to encompass a ‘whole ecosystem’ model – with (limited and relevant!) analysis of competitors, suppliers, customers and other third parties.

An Apology

The title of this discussion is a little misleading. In business, and more specifically in Finance, a black swan is an event or occurrence that deviates beyond what is normally expected of a situation and is extremely difficult to predict; the term was popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a finance professor, writer and former Wall Street trader.

Such events can be considered as unknown unknowns – we have no knowledge of the likelihood or even the possibility of their occurrence. It would, of course, be fanciful to suggest that enterprise business architecture enables us to deal with these comprehensively. However, a mature enterprise should be able to use EBA as a tool to shift the boundary between the unknown unknowns and known unknowns to its benefit. This has the effect of converting black swan events into known categories of disruptor, for which strategic responses can be devised.

In plainer language, mature business architecture will help us predict that relevant external disruptions might occur and, while not predicting that they will, at least allow us to plan for the eventuality, or even to encourage and nurture such disruption where it is advantageous.

The Role of a Mature Business Architecture Practice

A well-embedded, mature enterprise business architecture (EBA) practice fulfils several roles relevant to dealing with external disruptors:

- Horizon Scanning: being aware enough of the landscape in which the enterprise operates to be able to recognise and act upon relevant disruptive factors;

- Business Strategy/Architecture Alignment: ensuring that the strategic direction setting for the enterprise and the business architectures are consistent;

- Custody of the Business Architecture: the EBA practice is responsible for capturing, maintaining and communicating the knowledge and models which represent the current and future states of the business (for simplicity, we’ll refer to these artefacts collectively as the Business Model);

- Business/IT Alignment: ensuring that the architecture supports the needs of the business, as defined by the Business Strategy and EBA. This includes shaping and compliance of IT programs and projects put in place to meet those needs.

In general the way that these roles are fulfilled in large enterprises is not adequate for dealing with disruption. There are (at least) three areas of concern to be addressed, in a typical case:

- Horizon Scanning is performed in a limited manner (if at all). This is often done within pre-assumed boundaries, and with little focus on communicating the significance of their findings to the wider enterprise ;

- The business models lack depth. The knowledge that the BA practice gathers and maintains does not pay sufficient attention to traceability (e.g from business need to technical fulfilment), maintainability and ease of communication;

- The business model lacks breadth. In order to deal with disruption effectively, the business model must embody knowledge from an extended landscape, significantly beyond the boundaries of the enterprise. Often the EBA function (quite understandably) limits itself to a largely internal viewpoint.

Deepening the Business Model

An architectural business model should capture and formalise many aspects of the business itself, underpinning analysis, communication and common understanding across the enterprise. This is best achieved by combining and integrating a number of modelling techniques.

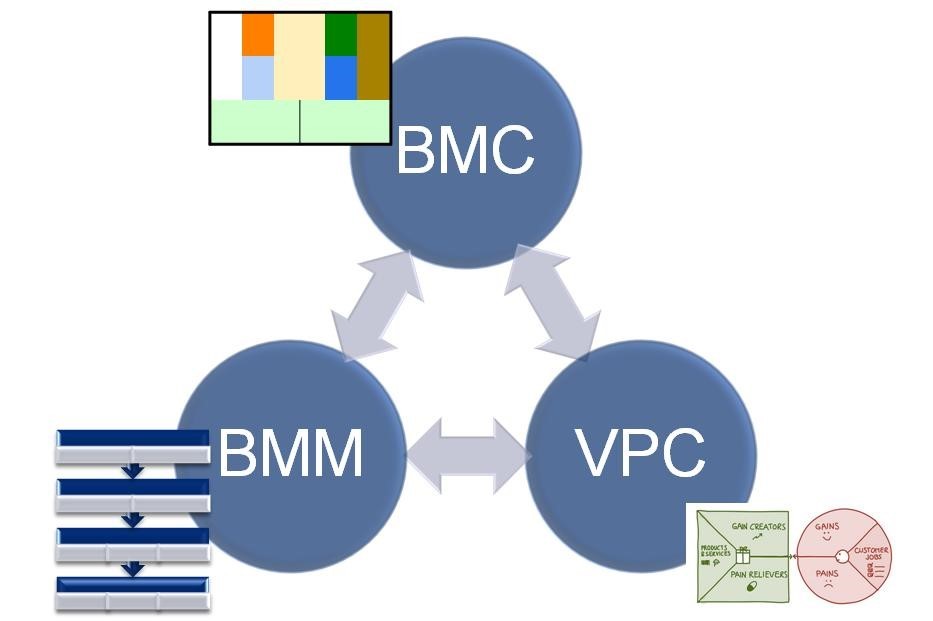

In practice, the development of a combined model, covers a great deal of the need. Elements of this combined model might include:

- Business Model Canvas (as developed by Osterwalder, Smith and Peigneur ),

- a Value Proposition Canvas (also developed by Osterwalder), and

- the Business Motivation Model from the Object Management Group

.

The Business Model Canvas (BMC) details the operations of the business, the resources to sustain operation, the products of that operation and the customers to whom these products provide value. It also details the costs accrued by and the revenues gained from these operations. In essence it tells us WHAT is required to run the business, and WHAT is produced.

The Value Proposition Canvas (VPC) gives us more detail about the operational reasons for the enterprise to do what it does (i.e. to produce specific value for specific customers). It details WHY the enterprise operates as it does, and FOR WHOM.

The Business Motivation Model (BMM) fleshes out the strategic reasons or the enterprise to exist (vision, goals, objectives, etc.). It details WHY the enterprise is in this business at all.

Business modelling should explicitly recognise the interdependencies between these techniques. The operational activity should reflect the provision of value to customers, which in turn should be aligned with the strategic aims (motivations) of the enterprise.

(This combination of techniques is not, of course, the only way of developing a comprehensive architectural business model, but we will use it as a suitable example for our purposes.)

Broadening the Business Model

Dealing with disruption architecturally nearly always involves taking a broader external perspective. The most robust way of dealing with this is to analyse the business models for major parties in your business ecosystem.

These parties will include:

- Participants in your supply chain – customers and suppliers

- Parties that exert a controlling or constraining influence on your business (for example, regulatory bodies or competitors)

- Parties that contribute to value delivery (key partners outside the direct supply chain, providers of resources used in value delivery, etc.)

The fundamental point behind this extra analysis is to ensure that knock-on effects of disruptors are detected in a timely manner. Many external disruptors will impact third parties in your ecosystem before they impact your enterprise. Reaction to changes in your customers’, suppliers’ or regulators’ business model will invariably be too late. The business architecture should have (at least) a limited perspective on these other parties models, and how they interface with your own.

At this point, you may be thinking that this will take superhuman effort from the Business Architects. However, for those whose professional focus is ‘upward facing’ (i.e. towards strategy) rather than ‘downward (i.e. towards IT), they will be provided with the collateral to become key business influencers.